Honesty lies at the core of much of what Saharu Nusaiba Kannari does, whether he’s writing or speaking. An honesty to one’s own self, of course, but an honesty in viewing the society, in creating messy and complex (aka realistic) characters, in discussing social truths (or lack thereof). It’s also why his (and his characters’) critical gaze brings forth truths we’d rather label “uncomfortable” or “impolite” and shrug off.

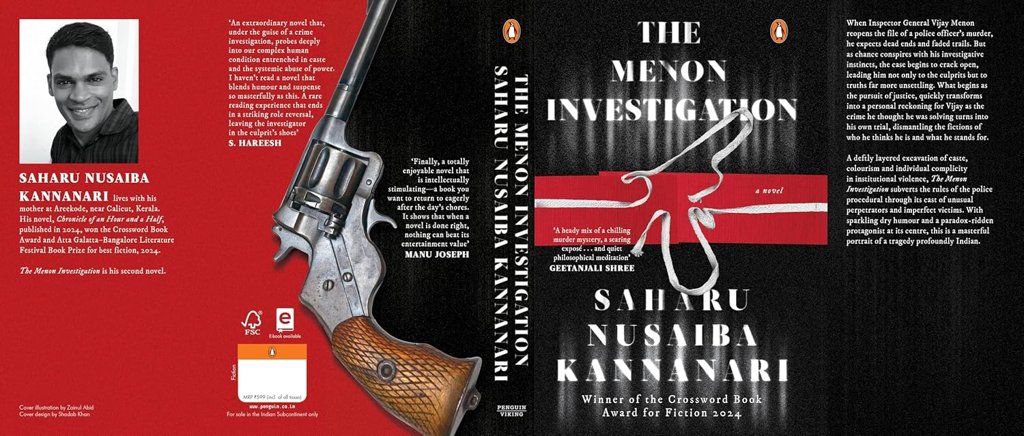

His latest, The Menon Investigation, is a novel that draws you deeper and deeper into an old reopened murder mystery and its complex entanglements in political corridors. Simultaneously, it pushes you toward a perhaps deeper complexity, that of the protagonist’s racial and casteist prejudices, prejudices that exist among all of us, deny though we may. Through an email correspondence, I got to interact with Saharu on the themes of the novel, on racial and caste discourse in popular culture, his perspectives on his characters, and a lot more. Enjoy:

Amritesh Mukherjee: What drew you to the crime thriller as a form? Were there particular influences—literary, social, or personal—that shaped your approach to the genre?

Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari: The philosophical thread running through the novel is millennia old: You are the person you want to condemn/pardon. However, the genre itself isn’t a result of any influence. I haven’t read any crime investigation novel in my life. That said, I’d admit that your question reminded me of a couple of movies I’d watched in my early twenties—Once upon a Time in Anatolia by Turkish director Nuri Belge Ceylan and Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion by Italian director Elio Petri. If the former more or less dwells in its own complex idiosyncratic way on the same philosophical adage I just stated, the latter is a satirical meditation on the extent to which the system—the police in this case—would go to deny the culpability one of its own staff to insulate its public reputation.

AM: Vijay Menon might be read as an unlikely—or even unlikeable—protagonist in the kind of discourse we have today. Yet his candour feels deliberate and productive, for it implicates social respectability and its polished hypocrisies, while also intensifying suspense as the fractures in his personal life align with the pressures of his professional one—extremely dissimilar tensions, extremely similar tensions. Your thoughts on the same?

SNK: Hypocrisy is self-aware. This is what makes judgement on a person possible. Denial of self-awareness, in fact, would amount to denial of agency, and denial of agency would render judgement impossible. However, since I harbour a healthy suspicion towards the power of a master’s in social sciences or scientific temperament in general to offer a sure vaccination against the crippling power of social systems like caste or patriarchy, the novel also humanizes its protagonist, who is as much a victim as he is a perpetrator.

So far as the question of likeability is concerned, well. I think both human wish and capacity to convert into practice one’s learned convictions is deeply strained by a host of social and psychological factors, and Vijay Menon is both sincere and helpless in his struggle. In other words, both the novel and the novelist are alert to the protagonist’s unavowability. But these are taboo subjects and would require a great deal of non-pretentiousness on the part of the reader to appreciate a book like this in all its complexity. I myself don’t approach my novels with words like likeability or relatability. I only treat them as realistic documents.

AM: The novel’s association of caste with colour is novel, for in upper-class, upper-caste spaces today, conversations around racism and colourism often detach themselves from caste, attributing prejudice solely to colonial influence. Do you see this distancing as a continuation—rather than a rejection—of casteism?

SNK: The association of caste and skin colour may be novel in terms of literary representation, but not as a lived reality. In a recent interview, I said that there is tremendous social expectation on the appearance of a body to give away one’s location in the caste hierarchy. I’d add that an egregious failure to meet this expectation sometimes attracts either derision or incredulity, the former usually reserved for an upper caste person with dark skin and the latter for a lower caste person with a fair complexion. In other words, it is not only enough that you belong to a caste. It is equally important to look like you belong to a certain caste. My novel satirizes this stereotypical expectation.

So far as the question of colonial legacy is concerned, I often recall what Ambedkar said about Congress in his submission to the Southborough Commission in 1919, that they are ‘Political radicals and social Tories.’ Which is why I believe it’s easier to be a secular than a non-casteist. India’s democracy has already successfully reversed whatever damage colonialism and anti-caste crusaders it had produced had done to our caste order. Post independent Indian state often reminds me of that famous sentence in the novel The Leopard by the Sicilian author Guisappe di Lampedusa, ‘Change everything a little so as to keep everything exactly the same.’

Look at the statistics. A staggering 80% of Indian Judicial officers from high courts to the Supreme Court are comprised of Savarnas who barely make up 20% of the population. This is true for the executive branch of the government and higher bureaucracy as well.

In a 2018 study on the caste segregation practices in India’s metropolises, authored by Naveen Bharathi, Deepak Malghan, and Andaleeb Rahman and published by IIM Bangalore, titled Isolated by caste: Neighbourhood-Scale Residential Segregation in Indian Metros says that 60% of the residential areas in the city of Kolkata don’t have a single Dalit resident. This is as good as apartheid, I suppose. Factor in also that Dalits make up more than 20% of Bengal’s population but somehow their population in the city is just 5%. And this is a state communists have ruled for 34 years.

In 1996, BK Uniyal famously checked the caste status of 700 accredited journalists in Delhi and couldn’t find a single Dalit among them. In 2010 Times of India reported that a Rajput family in Morena, Madhya Pradesh, excommunicated a dog, Sheru, and declared it untouchable because it ate a chapati offered to it by a Dalit woman. The Indian Human Development Survey, released in 2011, showed that only 5% of Indian marriages were inter-caste. These are random snapshots of the lived reality of caste in independent India, and I don’t think the British are responsible for it.

Now, to answer the specific connections between caste and racism, I confess that I don’t feel competent enough to engage the question. I am aware that Ram Manohar Lohia had written a couple of pieces on the aesthetic foundations of the caste system in a rudimentary fashion, but I am afraid I haven’t seen much highly nuanced scholarship on that front.

AM: Menon is self-critical, yet seemingly unable to extricate himself from the very social structures he investigates and condemns. From that perspective, would you describe the novel as pessimistic?

SNK: My novel is realistic, and realism is neither pessimistic nor optimistic. One of the reasons why I love my job as a novelist is its capacity to help me exorcise certitudes and opinions for a complex appreciation of the human condition, and I will continue to refuse to turn it into an emotional Amritanjan or cardiac therapy or intellectual khichdi even as I try to make it as entertaining as possible.

AM: I loved your story in Granta, A Public Circumcision. Do you plan to expand or revisit it in the future?

SNK: I am glad to know that. The piece that appeared in Granta is excerpted from my third novel in progress. I am hoping to finish it this year itself.

AM: What are you reading/watching currently?

SNK: The last movie I watched was in 2018. I am not reading much these days. I spend eight hours babysitting my niece. She looks like an extreme literary critic and has already torn into pieces two books, so my energy is largely spent on keeping books from her reach. But I did manage to read last month the first installment of Abhishek Choudhary’s brilliant two-volume biography of AB Vajpayee, Vajpayee: The Ascent of the Hindu Right, and Ioan Culiano’s The Tree of Gnosis: Gnostic Mythology from Early Christianity to Modern Nihilism. I also finally finished reading Anthony Sampson’s great biography of “The gregarious man with an impenetrable reserve”, Nelson Mandela. In literature, I am rereading Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author.